How has 2021 been for me? The answer lies predominantly in what it has no longer been, which requires some historical context.

Loneliness is a defining feature of the human experience. We were pulled into this world, into a skin that separates us, and, likewise, will be tugged from it.

Barbados’s buggery law (Chapter 154, Section 9 of the Sexual Offences Act criminalising “buggery,” with origins in 1533’s Buggery Act) compounds this separation by reducing male same-sex partnerships to an illegal sexual act. This, consequently, creates further barriers to how consenting grownups interrelate, through its bolstering of opinions resulting in homophobic behaviours like verbal abuse, including threats that have sometimes become physical. Living in Barbados as a sexual minority has been particularly challenging after residing in countries where my sexuality generally wasn’t a consideration for how strangers interacted with me, unless romantically interested.

Loneliness from isolation has worsened since COVID-19-related restrictions began in Barbados on March 28, 2020. Intellectually, I’d come to understand it’s a numbers game when hoping to meet someone who shares similar illusions about life. Accordingly, having experienced racism in its various—oftentimes blatant—forms abroad, and preferring the more easily ignorable Barbadian variety, I’d looked forward to making Ichirouganaim my home base and travelling to ‘safe spaces’ overseas where neither I nor potential partners feel the need to expend as much energy editing who we are, or being consistently guarded out of fear.

The prevalent dread of discovery of being a sexual minority had encouraged a ‘hook-up culture’ in Barbados long before COVID-19 decided I could not leave the island to pursue better opportunities for meeting well-rounded individuals. Here, there are no openly LGBTQ+ sanctuaries to sit close and have a conversation over a rum punch, no rainbow flags stuck anywhere suggesting this place or that is an “ally”, nowhere but those virtual platforms facilitating anonymity, often through ‘catfishing’, and perhaps leading to a necessarily quick, blanket substitute for equally meaningful forms of human intimacy.

This COVID thing! Just when, disgusted with algorithms stealthily teaching me to seek ‘likes’ by becoming plastic, I’d returned to meeting guys the old-fashioned way! By chance, in real life—eye contact, with increased risk of getting “chop” with a “big rock”, since, as a population, we seem to be aware we should be attempting to look ahead, while simultaneously remaining cemented in, or striding backwards into, anachronisms.

There were gay bars in Barbados in the late ’90s…well, at least one I frequented, Buddies. It hosted opulent drag shows and also offered a place you could be a Barbadian human, a recognised citizen who did not need, for their own safety’s sake, to look to see who was looking. There were also fixed party locations you could depend on for a last-Saturday-of-the-month release. Who knows the ‘Bull Pen’? (What a nickname!) And how dancing all night was an antidote to the depression accompanying my fugitive love life, and threatening to pin me to my bed.

Before COVID opened fire, there was already a monopoly of the LGBTQ+ party scene, locations shifting around like we were dodging bullets. I’d stopped going because the crowd gets younger as the entrance fees seem increasingly exploitative.

There was still a modicum of relief, however. I’d frequent an ‘everybody friendly’ bar in the city. Men, eyes inflamed with kill-devil, would offer words, in soft tones, saying they “don’t have anything against people like you”. They might also buy me an unsolicited drink and, later, ask for a ride home.

It was a secret in plain sight with circular tables to sit two or three, and lighting with only enough confidence to fully reveal the Deputies’ faces in the sponsored-beer fridges. I’ve always been drawn to these places where visitors—their presence—feels as if linked to mine, forming an invisible, impenetrable chainmail.

At the bar’s alter, I’d bow, take communion, the spirit would alter my perception and I am no longer good at saying when such and such a thing happened or that it did at all. Sometimes I’d think a word, yet say another. I’d surpass the daily recommended amount because someone else would buy a round, and you wouldn’t hear the end if you refused the courtesy.

Before we all wore literal masks, I would sing karaoke (oh, how I loved to sing karaoke), and, in my transformed state, I’d take myself seriously as a songster, closing my eyes to belt. Almost no longer ashamed that my voice only suits white boy bands, my requested songs were R.E.M.’s Losing my Religion, and Oasis’s Wonderwall and Don’t Look back in Anger.

It was a mixed crowd: desperados; alcoholics, including domino players; vagrants; ‘paros’ (soon to be chased off by the machete-wielding owner); sex workers (counting cis-men and trans-women); a mad man (or artist) wearing a beach umbrella; and older man-woman couples. In unison, we’d throw back our heads to sing oldie goldies.

Manifesting itself through pictureless profiles and pontificating online platform posturing, my heightened feelings are now of a movie character who does not know he is, in fact, a housebound spectre comprised primarily of memories of the life he used to live. This sensation is as persistent and prevalent as the pandemic. Yet, I remind myself there are surely others suffering more than I because they’re currently in worse forms of lockdown with very self-aware abusers.

Knowing this didn’t stop God befouling the entire country with volcanic ash from neighbouring St. Vincent’s La Soufrière in April this year, 2021. It drizzled down, blotting out the sun, confusing the birds (which returned to roost) and created a fittingly alien, nuclear winter landscape. This happened last in 1979, when my mother, seemingly quick to imagine me capable of the worst things, accused littler-me of throwing dirt on the clothes hung on the line in the yard, until she realised I must have been throwing it on the clothes in everybody else’s yard too.

Having a highly critical parent can undermine your sense of self-worth, especially if you live with them. However, being unable to escape them can also motivate you to learn alternative coping strategies. In 2021, I’ve become proficient at saying no and using WhatsApp to communicate. I am also re-framing the story child- me learned to tell itself, by examining the facts with new eyes and continuing to develop a strong conviction about who I really am, as different from my perception based on how I have been simultaneously relied upon for so much, but apparently incapable of completing tasks without correction.

What excites me is finally understanding that my parents may not have had the tools to break generational curses cast through inherited notions of indubitably abusive disciplinary practices; the perceived importance of appearances, so, my being wrangled into religiously saying “good morning” although a particular familial relationship doesn’t require I say anything else; duty; and unfounded respect for elders. However, their sacrifices have provided me opportunities to destroy the hex through, ironically, my understanding and compassion (including for myself). Now, I’ll overhear my father on the phone complaining about some opportunistic person he can’t say no to, while my autistic twin sister, in one of her moods, cries mournfully for a reason no one can identify, cuing my mother to burst into a drony Anglican hymn, and I’ll think, Not my circus. You can’t pour from a shattered tumbler.

With outside resembling a charcoal drawing, I gave up exercising the one day per week I’d managed to somehow trick myself into doing so outdoors. However, digging the volcanic cement from the roof runoff gutters was labour intensive and my night sleep, dreamless. It was reminiscent of my farm days in Costa Rica, resulting in me pondering the difficulty in switching mindsets when your wheels fit the grooves of well-established routine. Six months without internet at the farm, but it was easy because NO ONE WAS SCRUTINISING HOW I WALKED OR MOVED MY ARMS WHEN I TALKED and there were so many new experiences, with physical exhaustion heightening my interest in sleep by 8 p.m..

Before the volcano dumped its ash, COVID-19 had already obliterated the track with its agoraphobia; holding your breath when you walk past anyone; redefinition of public sneezing; all-day vaccination lines; supposed six feet apart-ing with strangers; awkward elbow knocking greetings with people you used to hug; hand sanitising and temperature taking; mask forgetting, and returning home to retrieve it; my obsessively checking my bank account; Zoom meetings; daily death tallies; creeping curfews; lockdowns and substantial increase in my backache from lying in bed binge-watching tv series.

Instead of posting on social media about this, I found comfort in the quick responses of invisible friends on continents to my messaging that I was learning to breathe volcanic dust. They said they were afraid for me, but I was too exhausted from my emotions accompanying the ever-changing COVID protocols to, myself, feel new trepidation—the ash only required more mask wearing and more staying indoors.

I turned to packing up (and dropping in the garbage cans by the gate) the junk from my father’s hoarders paradise. What pleasure this gives me now that age has exacerbated his self-involvement to the point of him not noticing, to then fret about it.

It is as if with the boxes go my childish attachments to the expectation that someone called a father is necessarily a father in more than just title. Piles of damp, yellow newspapers, freckled in mould, from as far back as the ’70s (some shredded into mouse nests) and pamphlets from a lifetime of him parenting meetings, workshops and conferences on education and credit unions. In one box, there was a toad whose story has turned to stone with it.

July would not be outdone. Initially monitored as a tropical wave, genderless, it made its solitary way westward, eventually becoming the first and earliest-forming fifth named storm on record in the Atlantic Ocean. The National Hurricane Center (NHC), designated it a potential tropical cyclone on June 29. On July 1, it would be called a tropical storm depression, then, after a few hours, be christened Tropical Storm Elsa, which may have caused it to rapidly intensify, becoming a Category 1 hurricane the following morning.

Elsa lick down trees, one across the road leading to an Airbnb residence I manage as my main income source. This happened a week before guests arrived and resulted in a chainsaw owner cutting up the mahogany tree and dragging a too-heavy- to-roll part of it, with his jalopy, onto a neighbour’s property without my immediate knowledge.

This neighbour then put his finger in my face, and I was tempted to WRING IT OFF through my Huey-Freeman-print mask with a bite, because the tree fall from a property whose unknown owner yuh can’ reach anyway ’cause he live somewhere overseas, and Chainsaw Man had already received he hundreds of dollars and wun answer he phone. Another neighbour said the first neighbour was “just being a Johnny” because there were several fallen trees on his property already, so you couldn’t tell the difference.

Elsa also visited, uninvited, where I live, and, with no malice in its heart, for no other reason than it being a hurricane’s nature to do so, it snapped branches, shook all the embryonic avocados from the tree in the yard and threw a television antenna to the ground with a slice of the roof, which hit me in the head on its way down.

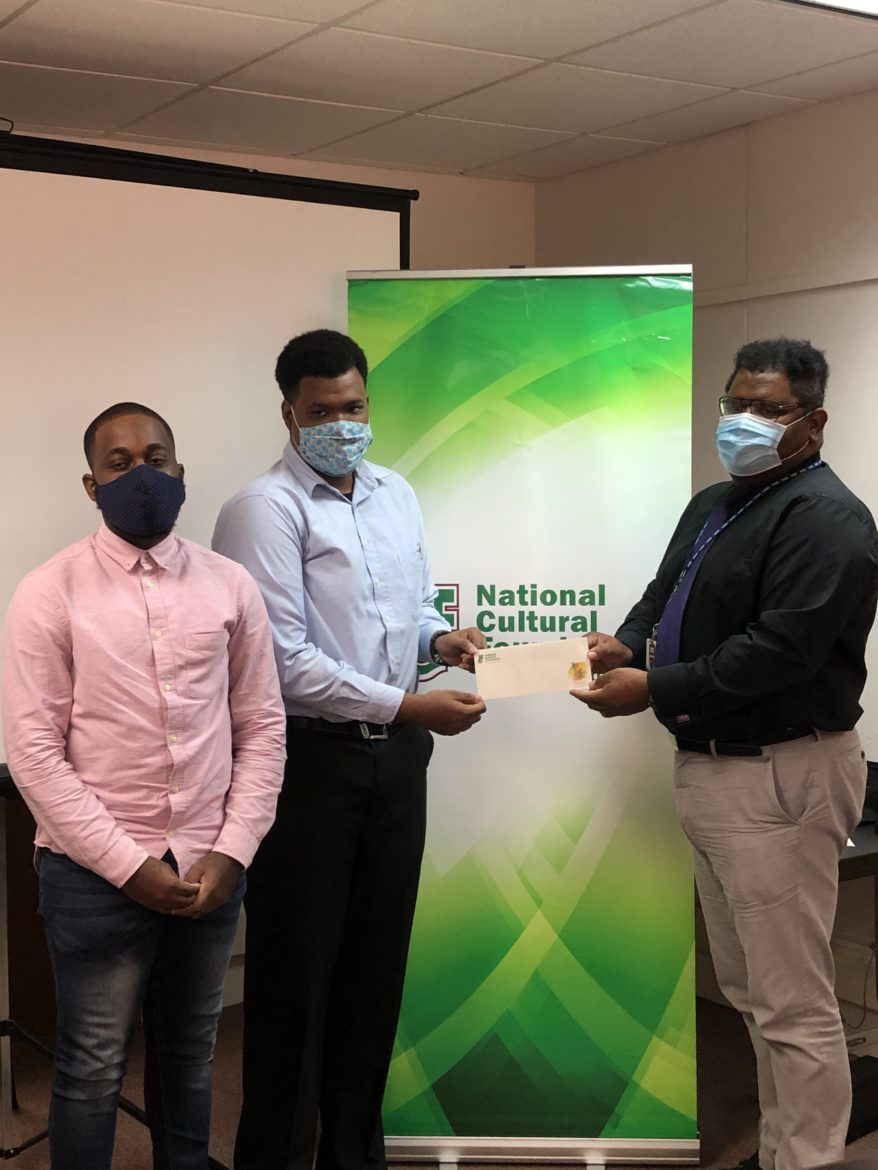

Seeing this, I laughed and laughed and laughed, only stopping when my tears made me hyperventilate. I have since permanently quit listening to the news in favour of, among other things, wondering if Barbados’s National Cultural Foundation sent an email, that was accidentally directed to my spam folder, regarding the future of the NIFCA Literary Arts Competition; reading drafts of stories like this one out loud, while making the floorboards creek from pacing; fitting my feet into strangers’ footprints on the beach; wandering my kitchen garden at night, searching for slugs; and blowing gently on candle flames and lavender incense smoke, as I soak myself in the bathtub.